Querying The World: Developing Systemic Literacy In Early Elementary

- Kara Fleshman

- May 9, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 9, 2025

The problems of today are systemic problems, which means that they are interconnected and interdependent ~ Fritjof Kapra

The relevance and importance ‘systems thinking’ in schools is nearly limitless. Pick any level, lens, or sector of education to analyze and you’ll find multiple systems at work.

In my TK, Kinder, 1st and Second grade classes we are often surprised and energized to follow the thread and see how deep the lens of a system can really take us.

Reading ‘system’ might evoke thoughts around systems of inequality, of systems of oppression and subjugation, of school systems, of nervous systems, of digestive systems, of solar systems, or any and all of these together, interacting. Those evocations all make sense. The beauty of the lens is its reach.

Systems can take our gaze wide and far, or can hone it in with tremendous detail. Systems can be material, small, and seemingly discreet...like an ant. Traditional science curriculums might have us name an ant’s body parts...draw and label them...and classify the ant within the ‘animal kingdom’. Teachers going ‘above and beyond’ to do something hands-on might even give students the chance to look at a real ant with a magnifying glass. Some students might find a new found fear or love for ants, some might wonder what happens when you squish them, some might remember the magnifying glass and forget the ant when retelling what they did in school that day. But in most curriculums, in most classrooms, our 5 year old scholars wouldn’t get the opportunity to marvel at and question the real magic of the ant in context….the internal regulatory systems that keep the individual ant alive, breathing and growing, the social system that supports it, the human centered systems that the ant system overlaps with, the Eurocentric taxonomical classification system that defines for ‘science’ where the ant lands within the proposed hierarchy, or even more, how that system came to be, how its been weaponized throughout history, and how it confirms or conflicts with knowledge systems that Eurocentric westernized ‘science’ considers ‘other’.

Systems tell the stories that the ‘facts’ alone leave hanging. What is the value of knowing how to name my bones and my internal organs without considering how my skeletal system, nervous system, and respiratory system support one another? Or how our food systems and health systems and social systems support my body system, or the bodies of my family, my neighborhood, and community as a whole, and in comparison to families, communities and neighborhoods across the globe?

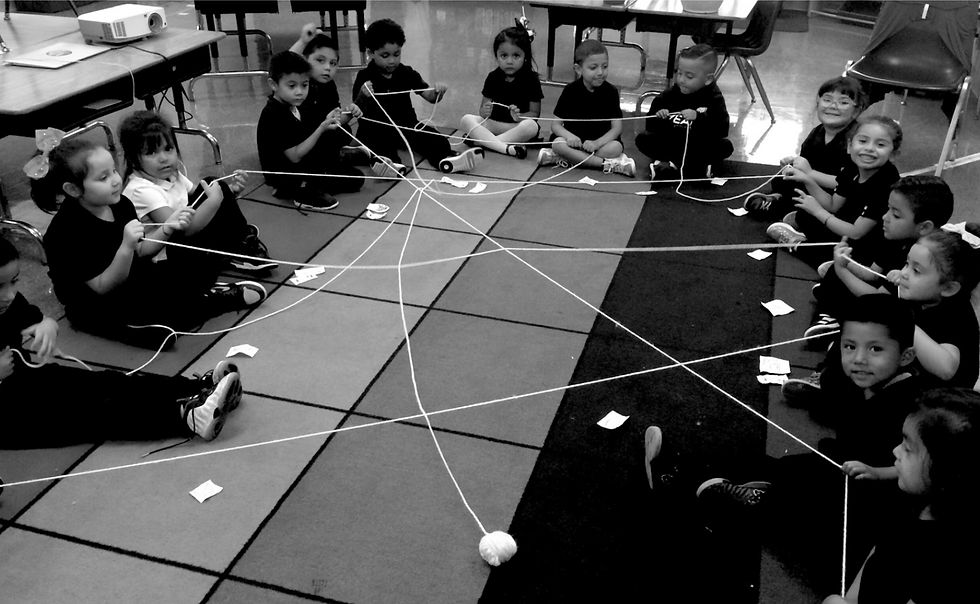

Through focusing on the specificity and detail of a system's components and on interactions and connections between them, system thinking can tell the story of our value. Each piece of the system plays a role, has an effect, brings a unique twist, and that twist impacts and is impacted by the whole.

We cant get see and appreciate and work with these wholes if we keep teaching by isolating, be that the isolation of content areas (separating reading and writing and history and science and math and art), isolation of the content itself (learning the ant as the unit of study, without the context of its colony, its interactions with human systems etc...learning the units of a sentence), and even isolation of us within the classroom and school (the teacher holds the knowledge, each student is responsible for their own absorption of what the teacher puts out, ‘restorative justice’ is your job, social emotional is yours, math is mine etc)

While our students learn to name and define, they can also learn to question, to interact, to consider the unseen, to understand the connections. When we break out of our 15 minute ‘social emotional time’ blocked out plan and consider that this learning is daylong and lifelong (and apply our same thinking skills from ‘science’ and ‘art’ and ‘history’ to the classroom and the community as a social group), we as a group of people, are much closer to being able to analyze and understand and problem solve. The weight of this thinking and acting is not only on the shoulders of the teacher, but distributed across the smaller system within the room, the larger system within the school, the community outside the school, and on and on.

Looking at the world through the systems lens takes you deep, to a place of connections and contradictions and beauty and pattern and perfection and messiness that students from TK to Post Graduate school can connect to. The lens of a system, as Freire so clearly said, help us with those discreet skills like learning to read the word in service of a much more important goal, reading the world.

The basic question in school is how not to separate reading the word and reading the world, reading the text and reading the context. ~ Paulo Freire

Context is always key. Its in looking for it, analyzing it, and considering it that we start to build the muscles and neurological pathways for critical thinking.

So why put all of our energy into separating, isolating and rationing out discrete information and ‘facts’ over the course of a student’s schooling experience? We often see daily schedules and curriculum plans in Kindergarten and First Grade dedicating 15 minutes to ‘Social Emotional Learning’ each morning before sectioning the rest of the day into short, discrete segments for drilling skills in phonics, numeracy, vocabulary dissection, and play. As students get older, the day stays segregated, and they begin to go to different rooms for discrete skills. Here we compare and contrast. Here we multiply. Here we exercise. Here we write. Here we follow the steps to an experiment. Here we ‘build community.’ This is how the system is structured, to disconnect. It takes tremendous extra work for teachers to blur those lines... to collaborate, to build a through line, to contextualize.

As a ‘specialty prep teacher’, someone who gets to teach all the rest of the stuff... the subject areas the state has yet to measure and judge which the system then chooses not to prioritize. Im take all the leftover subjects. Science, Art, History, Physical Education. Its in this context, with no mandated minutes, no curriculum to work off of, and an inherent distaste for attempting to isolate the subjects from each other and the students from the content and the context, I’ve had the beautiful opportunity to experiment alongside my students to reframe our whole class. Systems has been our anchor. With this as the foundation, we’re able to welcome new information and experiences of all kinds and sharpen our skills of analysis, understanding, questioning, problem solving, and dreaming. We marvel in the details of the individuals at the same time as we learn from their interactions. We wonder about origins and endings. We question why is this so, and does it always have to be that way?

We believe that we cannot deeply improve science learning and identification with science without querying science and science education as a set of cultural practices ~ Megan Bang and Douglas Medin

The systems lens helps me look for and catch my own Eurocentric taxonomical tendencies...It stops me at every turn and asks me...What makes me think this content or activity from my training or schooling experience is worth repeating? Where does this idea/activity/framing come from, and where might that lead us?

The lens of the system helped me throughout what truly felt like a battle, the process of earning a Masters and ‘Clear Credential’ while needing to perform research on my students in the classroom. It helped me situate the thesis assignment and the research process itself within a history of deficit minded, predatory science. It helped me pull apart the research process to reveal its pieces while seeing how those pieces served the whole.

I battled with the primary piece, the ‘problem statement’, throughout the entire course of the year and the research. The process asked me to name a problem, then develop and test an idea to fix it. According to the program, the problem I started picking apart (our school’s material valuing of discrete reading and math skills over all else, the challenge of holding the responsibility of all the ‘subjects’ that fall outside of those discrete skill areas in very short time block with 7 different classrooms of students across 4 grade levels, the fact of no available accessible curriculum that bridges, unites, and historicizes the disciplines, the lack of resources geared towards critical thinking, systems thinking skills, and science grounded in non-Eurocentric epistemologies in the lower grades) was not valid because it was too systemic. For them the problem had to fit squarely within the confines of my classroom, the ‘research site,’ and even then, the problem couldn’t be me, it couldn’t be the texts on my shelves, it had to be the ‘subjects’ of my work. It had to be the students. The whole premise required me to a priori find something wrong with the students that I could improve on.

It was through twisting and flipping and fighting this process all along the way that I became even more firmly grounded in my belief, through reading and research but most importantly through experience and observation and interaction, that our students come to school critical, they come to school curious, they ARE systems thinkers. They look for wholes and analyze parts, they compare and contrast, they relentlessly seek justice and understanding, they carry within them what Zaretta Hammond in her work on Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain calls an ‘intellective capacity’. The problem is not their lack, its first the explicit and the subtle and the consistent ways that the things we choose to teach and the ways we choose to teach them work together to push and hold those intellective doors closed, and then second the stuckness of turning dependent into independent thinkers after we’ve successfully repressed that disposition. We shut down students’ natural curiosity, their natural tendency to look for any analyze things systemically, and then wonder why they don’t appear to be interested or engaged, why they look to us for answers, or look around for an easy way out.